- Home

- Mario Mieli

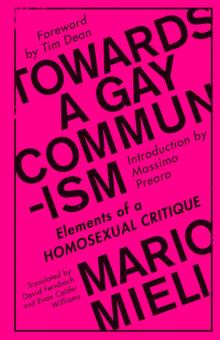

Towards a Gay Communism

Towards a Gay Communism Read online

Towards a Gay Communism

© « » Ä à â ä ç è é ê ì î ï ñ ò ó ö ø ù ü Œ # Ž ž & < > ῖ – — ‘ ’ “ ” … α δ η θ ι ο π ς σ

Towards a Gay Communism

Elements of Homosexual Critique

Mario Mieli

Translated by David Fernbach and Evan Calder Williams

Introduction by Massimo Prearo

Foreword by Tim Dean

First published as Elementi di critica omosessuale in 2002 by Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore, Milan, Italy

This edition first published 2018 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Copyright © Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore, 2002; revised English translation

© David Fernbach and Evan Calder Williams 2018

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 9952 2 Hardback

ISBN 978 0 7453 9951 5 Paperback

ISBN 978 1 7868 0053 4 PDF eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0055 8 Kindle eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0054 1 EPUB eBook

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England

Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America

Contents

Foreword: ‘I Keep My Treasure in My Arse’ by Tim Dean

Introduction by Massimo Prearo

Translator’s Preface by Evan Calder Williams

Preface

1. Homosexual Desire is Universal

2. Fire and Brimstone, or How Homosexuals Became Gay

3. Heterosexual Men, or rather Closet Queens

4. Crime and Punishment

5. A Healthy Mind in a Perverse Body

6. Towards a Gay Communism

7. The End

Appendix A: Unpublished Preface to Homosexuality and Liberation by Mario Mieli (1980)

Appendix B: Translator’s additional note from Chapter 1

Index

Foreword

‘I Keep My Treasure in My Arse’

Tim Dean

Rereading Mario Mieli today, I am catapulted back to the time when I first encountered his manifesto, published then in an abridged version under the title Homosexuality and Liberation by London’s Gay Men’s Press in 1980. I read Mieli alongside other works of gay liberation, psychoanalytic theory, and feminism during those heady days of university in the late eighties. AIDS cast a shadow, but not dark enough to obscure the radical ideas that were expanding the consciousness – if not completely blowing the mind – of this first-generation college student from the provinces. Mieli’s book wasn’t part of any syllabus; there were no gay studies or queer theory courses at universities in those days – though there would be soon. We were gearing up to invent queer theory, and Mieli offered a template for how it might be done. Yet because queer theory turned out to be ‘Made in America,’ its European history was largely erased. Reconsidering Towards a Gay Communism now, in this unabridged English translation, provides an opportunity to rewrite the origin myth of queer theory and politics in a more international frame.

Although I was unaware of it then, the world from which Mieli’s book emerged had vanished almost completely by the time I came upon it – and Mieli himself had committed suicide in 1983. The 1980 English edition gave no hint of these changes. Nothing dates Towards a Gay Communism more than its unavoidable ignorance of AIDS, which initially gained medical notice in 1981 but was not named as such until a year later. The onslaught of the epidemic and the reactionary political climate of the eighties altered gay liberation’s trajectory in ways Mieli couldn’t have predicted or foreseen. In hindsight, the divide between pre- and post-liberation eras of gay existence (conventionally denoted by the date June 1969, when drag queens and others fought back against police persecution at New York’s Stonewall Inn) was matched barely more than a decade later by the chasm that opened between pre- and post-AIDS epochs of gay life. Mieli wrote during that glorious decade of gay liberation, when so much seemed newly possible. His book is a testament to an era that already felt a lifetime away for gay men of my generation, who came of age during the eighties and thus never knew sex without the attendant pressure of mortality. Having no direct memory of sex in the seventies, I remain fascinated by accounts such as Mieli’s that capture those years so ebulliently. Towards a Gay Communism documents a crucial historical moment, at the same time as it offers fresh inspiration for us today.

Mieli articulated something that has mostly got lost in contemporary queer theory: the foundational significance of sex. He put his finger on the cultural antipathy towards anal sex – an antipathy that the AIDS epidemic intensified, that Leo Bersani1 analysed ten years after Mieli, and that paradoxically, queer theory’s newfound respectability has compounded:

What in homosexuality particularly horrifies homo normalis, the policeman of the hetero-capitalist system, is being fucked in the arse; and this can only mean that one of the most delicious bodily pleasures, anal intercourse, is itself a significant revolutionary force. The thing that we queens are so greatly put down for contains a large part of our subversive gay potential. I keep my treasure in my arse, but then my arse is open to everyone . . .

The most marvelous thing about Mieli is that he really seems to mean open to everyone. Although the HIV/AIDS epidemic cast a pall over the original joie de vivre of such sentences, Mieli’s stance embraces risk even without the spectre of viral transmission. The risks of bodily porousness and radical openness to the other remain, both before and after AIDS.2 Appreciating the ethics of Mieli’s stance, we should not miss how playfully flirtatious his punctuation is here. The ellipsis that ends the last sentence quoted above – and, in fact, closes the chapter in which this passage appears – issues a provocative invitation: my arse is open to you too, if you’re interested. He leaves the sentence open-ended to signal that his own rear end stays open. His butt offers a welcoming smile to the reader.

This gesture of openness to all comers betokens Mieli’s radically democratic ethos. The socio-erotic economy he envisions under gay communism is about not sexual identity but erotic abundance, a world in which artificial sexual scarcity would be unknown. Based on a liberationist model of queer sexuality, Mieli drastically redefines communism as ‘the rediscovery of bodies and their fundamental communicative function, their polymorphous potential for love’. In this almost Bataillelike communication of material forms, human corporeality enters into egalitarian relations with all worldly beings, including ‘children and new arrivals of every kind, dead bodies, animals, plants, things, flowers, turds . . .’ Again the sentence ends with ellipses, this time to indicate that the list could continue. And again the beautiful (flowers) is juxtaposed with the ugly (turds), anticipating the transvaluation that crystallises in Mieli’s announcement, ‘I keep my treasure in my arse.’

Turds may be regarded as treasure rather than waste because embracing queer sexuality (instead of merely tolerating it) upends the entire hierarchy of value and propriety upon which social convention rests. According to Mieli, once the full significance of homosexuality is grasped, the meaning of everything changes. He could not have anticipated how normalised gay identity would become in the twenty-first century. Mieli’s vision aims to restore to adult life the ‘polymorphous potential for love’ that characterises childhood, before categories of identity assume their disciplinary weight. In the

polymorphous pleasures of gay sex, particularly its desublimation of anal play, Mieli glimpsed the possibility that we all could return to a prelapsarian state of erotic grace, forging a utopia in which not only our arses but our most intimate beings would be open to otherness. His commitment to this vision anticipates recent queer utopianism – with the difference that he does not shy away from sex.3

Mieli’s conviction about the potential of Eros goes further than most queer critiques, since he includes pedophilia, necrophilia, and coprophagy in his catalogue of experiences ripe for redemption. Needless to say, this is explosively controversial, more so now than in the 1970s. I find his commitment to thinking beyond the limits of revulsion particularly refreshing today, at a moment when the gay movement has become so domesticated and respectable. For me, Mieli’s courage in pursuing his thesis way beyond socially acceptable parameters recalls Freud’s moral and intellectual bravery on erotic matters. The excitement I feel reading Towards a Gay Communism recalls how I felt when I first read Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, especially in its original, 1905 edition. Mieli’s was one of the earliest radical interpretations of that indispensable Freudian text, and many of his claims anticipate subsequent readings of Freud by Italian queer theorist Teresa de Lauretis and thinkers such as Leo Bersani. It takes a fundamentally non-American perspective to see what a valuable resource – treasure, even – Freud can be for queer politics.

Regarding psychoanalysis, Mieli saw that its institutional avatars could not legitimately lay claim to Freud’s most important insights. Instead, it was up to the women’s and gay liberation movements to elaborate the implications of Three Essays, paradoxically in opposition to the mental health establishment. This project continues on many fronts today, in the work of feminists and queer theorists who read psychoanalysis against itself, often from a position outside psychoanalytic institutions.4 Given Mieli’s own experiences at the hands of the ‘psychonazis’, it is all the more to his credit that he was able to distinguish the radical potential of psychoanalytic concepts from the repressive practices of those who routinely invoke Freudian authority to bolster their homophobic and normalising agendas. As a queer psychoanalytic thinker, I appreciate his acknowledging how psychoanalysis ‘flinches from the logic of its own insights, from drawing “extreme” theoretical conclusions’. Mieli grasped that psychoanalytic thinking represents an unfinished – perhaps an interminable – enterprise and, indeed, that too many analysts remain inhibited by professional decorum from pursuing the unsettling implications of Freud’s ideas about sexuality. Freud’s observation that ‘all human beings are capable of making a homosexual object-choice and have in fact made one in their unconscious’ tends to be hastily cordoned off from serious investigation by clinicians.5 Whereas institutionalised psychoanalysis domesticates the conceptual wildness of the Freudian text, Mieli labours to queer it, drawing out the productively incoherent logics of psychoanalysis.

Redefining from a radically gay perspective the established meanings of both psychoanalysis and communism, Mieli’s book belongs to the Freudo-Marxist tradition of political thinking that includes such various figures as Herbert Marcuse, Guy Hocquenghem, and Slavoj Žižek (whose writing manifests a camp sensibility congruent with Mieli’s queeny wit). Unlike some thinkers in the Freudo-Marxist tradition, however, Mieli has no patience for Lacan, preferring instead Deleuze and Guattari’s anti-Oedipal critique of orthodox Lacanianism.6 But what really distinguishes Towards a Gay Communism methodologically from queer theory – even as the book continues to provide inspiration today – is its omission of the work of Michel Foucault. The introductory volume of Foucault’s History of Sexuality appeared in France in 1976, too late for Mieli to take stock of it in a book that reached print just a few months afterward.7

Foucault’s introductory volume ended up functioning as a primary source for what became Anglo-American queer theory in the nineties. It was the basic idea of sexual repression – a linchpin of Mieli’s thesis – that Foucault sought to challenge in that polemic. If society does not repress desire but instead provokes it by means of proliferating discourses on sexuality, then the whole project of liberation is thrown into doubt. While Mieli wasn’t a specific target of Foucault’s critique, Towards a Gay Communism got swept up in its dragnet. His account of how heterosexuals repress their inner homosexuality can sound naïve in the wake of Foucault’s argument. Since Foucault aimed to wrest discussion of sexual politics away from the terms of the Freudo-Marxist tradition, the success of his book inadvertently cast Mieli’s into shadow, obscuring its significance for early practitioners of queer theory and politics.

This accident of publication history also has obscured all the ways that Towards a Gay Communism nevertheless anticipates queer theory. In his thoroughgoing critique of the heterosexual norm, Mieli is closer to Foucault and to many contemporary queer theorists than initially he appears. As a result of his commitment to revolutionary rather than reformist politics, Mieli develops a view of society that prompts him to argue not simply against heterosexism but, more broadly, against the institutions of normality as such. He sees that gay identity itself can serve the forces of normalisation and that something more radical is necessary. Like Foucault, Mieli recognises that sexual behavior is regulated as much by social norms as by laws; the repeal of anti-sodomy legislation can actually intensify the social normalisation of sexuality, as is arguably the case in the United States after the Supreme Court, in Lawrence v. Texas (2003), invalidated sodomy statutes. That was a great victory, but it didn’t solve everything for queers. Late in his manifesto, Mieli assures straight readers that ‘we are not struggling against you, but only against your “normality”.’Today we would say that the problem is not heterosexuality but heteronormativity. Mieli lacks the term, but he intuits the concept.

Likewise he takes the term gay beyond the coordinates of identity. Too often today, as queer is used merely as a hipper synonym for gay, queerness gets reduced to an identity marker. Mieli’s logic works in the opposite direction, by loosening gayness from an exclusively sexual orientation to something more capacious. Sexual orientation is itself a normalising idea whose temporary benefits he could see past even in the seventies. In this respect, Mieli was considerably ahead of his time. He understood that shoring up lesbian or gay identities in opposition to heterosexuality misapprehends how identity categories themselves constrain subjectivity, desire, and relationality. It is not the particular content of any identity category but identity as a form of intelligibility – a framework governing our understanding – that limits us in so many ways. We need a revolutionary perspective now, no less so than in the seventies, to break apart the comfortable boundaries of identitarianism. We don’t need a proliferation of gender and sexual identities, as many contemporary queers seem to believe, but instead to obliterate the mindset of identity altogether.

Mieli adopts from Wilhelm Reich the derisive term homo normalis to designate those who – whatever their gender or sexuality – remain committed to the status quo. Today the term applies to all those homos who want nothing more than to get married and ‘be normal’. It would have been interesting to hear Mieli’s view on the campaign for same-sex marriage and its impact on those of us who eschew the white picket fence. When assimilationist gays pass as normal, presenting themselves as ‘just like everyone else’, the social pressure to comply with normative models intensifies against anyone who still counts as queer or somehow beyond the pale. In other words, the social opprobrium that gay conformists manage to evade does not simply disappear. It falls with greater weight on the transgendered, sex workers, leatherfolk, SM enthusiasts, HIV-positive people, fetishists – all those who still are stigmatised by sex/gender norms. Mieli, like queer theorist Michael Warner, perceives acutely ‘the trouble with normal’.8

If he were writing today, Mieli doubtless would present himself and his perspective as queer. No small part of the force of Towards a Gay Communism stems from its author’s explicit desire not

to be normal, his delight in being a ‘crazy queen’, flamboyant and outrageous. Much of the book’s pungency comes from Mieli’s capacity for being intellectually serious and very funny at once – as in his line about keeping his treasure in his arse. His book is psychoanalytic not only in its conceptual formulations but also in its understanding that comedy offers a unique form of insight. Mieli’s humour frequently targets gender norms, especially those of machismo. In his time and place, a primary way not to be normal was through cross-dressing, or what today we might call genderfuck, a stylistic means of disrupting the categories of gender normativity to unsettling and often humorous effect. The point is not to conform to – or make fun of – the ‘opposite’ gender, but to highlight the absurdity of every attempt at gender conformity.

Given transgender politics today, we need to think about how Mieli uses the term transsexuality. Borrowing from Luciano Parinetto, he develops this term quite differently from contemporary usage. Whereas today transgender concerns above all questions of gender identity, for Mieli transsexuality has more to do with erotic desire than with gender presentation or performance. He may talk, in Towards a Gay Communism, about the mischief that cross-dressing gay men can do to the normative social order, but that is not what Mieli means by transsexuality. It is necessary to clarify this distinction since the term he uses affirmatively now connotes pathology – or at least is understood by most transgendered people as pejorative. I’ve suggested that today Mieli would present himself as queer; but I believe he also would be involved with trans activism. He’d grasp the connections between queer and trans, while also acknowledging the strong political tensions between them. I cannot imagine what pronoun Mieli would choose for himself, though I’m confident he’d be alive to the issues involved in pronoun usage, and I’m hopeful that trans readers will draw inspiration from his thinking, as queer readers continue to do.

Towards a Gay Communism

Towards a Gay Communism